- 1. Introduction - Critical Analysis of Social Work Intervention Approaches in a Placement Setting

- Placement Setting: Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care

- Significance of the Client Group in Social Work Practice

- Legal and Ethical Responsibilities in Adult Social Care

- Challenges in Service Delivery

- The Importance of Interdisciplinary and Multi-Agency Collaboration

- 2. Policy and Service Delivery in Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care

- Legislative Frameworks and Their Influence on Service Delivery

- Impact of Policies on the Structure and Delivery of Services

- Challenges and Opportunities within the Policy Framework

- 3. Analysis of Theories and Methods of Intervention

- Strengths-Based Approach

- Application in Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care

- Narrative Approach (Crisis Intervention Framework)

- Comparison of the Two Approaches

- Differences in Focus and Application

- Effectiveness in Addressing Client Needs

- Strengths and Limitations of Each Approach

- Use of the Two Approaches in Social Work Practice

- 4. Review of Social Work Literature

- Strengths-Based Practice in Adult Social Care

- Narrative Approach in Crisis Intervention

- Gaps in Research and Future Directions

- 5. Critical Distinction Between Knowledge Types

- Theoretical Knowledge in Social Work

- Practice-Based Wisdom

- Evidence-Based Practice in Social Work

- Reflective Knowledge and Self-Reflexivity

- Service User Knowledge and Lived Experience

- 6. Conclusion

- Practical Implications for Future Social Work Practice

1. Introduction - Critical Analysis of Social Work Intervention Approaches in a Placement Setting

Placement Setting: Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care

My last placement in social work was in Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care, a statutory body of adults who use the service in social care as they age through the maturation of their disability or other vulnerabilities (Tower Hamlets, 2025). This service falls within the framework of the Care Act 2014 and other associated legislation, and it is used in the assessment, the intervention and the provision of support to help individuals maintain their well-being and independence. In this context, I served as a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) member working with healthcare professionals, housing services and voluntary sector organisations in a holistic delivery setting.

Significance of the Client Group in Social Work Practice

It has one of the UK's most diverse and economically deprived areas: the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. There is a high degree of social inequality, poverty, and an ageing population with a need for care and support. Given the complexity of needs within this community, adult social care is a vital part of today’s contemporary social work practice. First of all, the growing ‘ageing population’ brings a higher need for social care services, especially for those people who require care due to their mobility problems and mental or physical problems.

Legal and Ethical Responsibilities in Adult Social Care

Several legal and ethical responsibilities influence social work practice in adult social care. Local authorities’ duty under the Care Act 2014 is to assess needs, prevent harm, and promote well-being (Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2024). The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) is important as it tells us how people who lack capacity can be planned for and how they can be cared for and have decisions made for them in their best interest. The Equality Act 2010 also reinforces that services are provided without non-discriminatory access and that this access is provided equitably to all people in need of support (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2020).

Challenges in Service Delivery

Social care services in Tower Hamlets face several challenges. Service provision is severely hampered due to resource constraints and barriers to timely intervention. Another issue complicating digital exclusion, particularly for older service users, is their difficulties with technology services, which means they cannot access digital resources, benefits, and telecare solutions (Frishammar et al., 2023).

The Importance of Interdisciplinary and Multi-Agency Collaboration

The placement also highlighted the significance of interdisciplinary and multi-agency working in bringing about effective social care. Service users were given comprehensive and coordinated care, working closely with health professionals, housing services, charities and advocacy groups (Frishammar et al., 2023). Integrated care models have been key in delivering improved outcomes, centring around a person-focused holistic approach that customises support to individual needs (Isaacs and Mitchell, 2024). It presented an insight into the complexities of adult social care provision, policy-driven practice and the intervention strategy to protect and empower adults at risk. The following sections critically examine the policies, interventions, and theoretical frameworks underpinning social work practice in this setting.

2. Policy and Service Delivery in Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care

Legislative Frameworks and Their Influence on Service Delivery

Adult social care practice is governed by legislation, policies, and local protocols that determine how the service is structured and provided. Statutory responsibilities within Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care are underpinned by key national legislations: Care Act 2014, Mental Capacity Act 2005, Equality Act 2010, and also Home Office Gateway 26 and Homelessness Prevention Essential (UK Government, 2018). Legislative frameworks identify the rights of service users and social workers’ responsibilities and force principles of safeguarding, autonomy and well-being.

Figure 1: Different Frameworks related to service delivery procedures

Adult social care is primarily legislated under the Care Act 2014, which places a duty on local authorities to assess, plan and deliver services in line with an individual’s needs. The Act requires the development of support for adults based on their personal needs (Atefi et al., 2023). The Act heavily depends on well-being in that social workers should prioritize factors like dignity, control of everyday life and social and economic participation. In addition, this legislation encourages prevention and early intervention, aiming to avert the necessity of crisis dispensation services through proactive support (Byrne and O’Mahony, 2020).

Therefore, when individuals cannot make an informed decision, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) is vital (Ariyo et al., 2021). Tower Hamlets IS an area where a large number of service users have cognitive impairments (including dementia, brain injury or learning disabilities) where thorough capacity assessments are needed. The MCA guarantees that decisions about people concerning them are based on the principles of least restrictive intervention and best interests (Atefi et al., 2023). It also sets out the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS), making all restrictive care arrangements lawful and proportionate.

The MCA closely relates to the Equality Act 2010 and thus strengthened anti-discrimination laws to protect service users from unfair treatment on the grounds of age, disability, gender, race, and other protected characteristics (Atefi et al., 2023). In practice, this legislation achieves equitable access to care services, and reasonable adjustments are made for people with disabilities.

Impact of Policies on the Structure and Delivery of Services

The policies determining the structure, design, or delivery of adult social care services in Tower Hamlets are essential. Care Act 2014, Mental Capacity Act 2005 and Equality Act 2010 are the legal frameworks with the principles, responsibilities and procedures governing social work practice (House of Lords, 2019). Government strategies on integrated care, telecare and digital inclusion influence how to provide services to adults with social care needs. Under the Care Act 2014, local authorities are required, through a structured approach,h to assess and meet eligible care needs (House of Lords, 2019). This legislation means social workers must service users and consider their strengths, preferences, and aspirations when planning care.

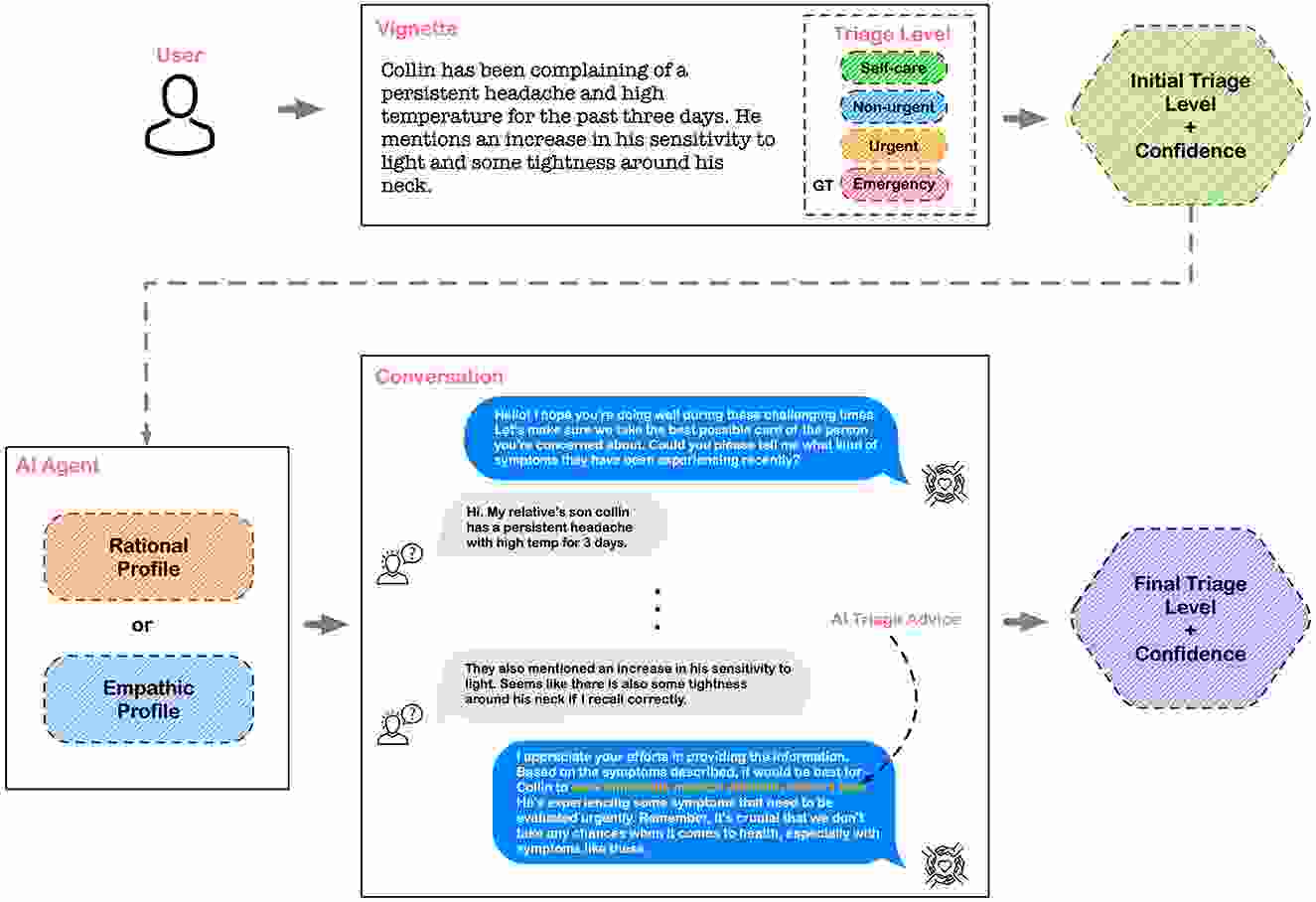

Figure 2: Different factors associated with community service

Prevention and early intervention are among the most significant changes introduced by the Care Act. It encourages social care teams to help with prevention rather than crisis so that people need less costly long-term interventions such as hospital admissions or residential care (SCIE, 2022). In practice, this has propagated the development of preventative services such as community-based support, voluntary sector partnerships, and assistive technology solutions. However, budget constraints frequently prevent preventive services from receiving the funding they need, so they are not necessarily proactive but rather reactive.

Much of the way services are delivered, both here and abroad, has been influenced by the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) – particularly concerning providing support to adults with dementia, learning disabilities or acquired brain injury (SCIE, 2022). The Act states that social workers must given assessed capacity on a decision-specific basis and, wherever possible, assist people in making their own choices. Applying MCA principles in Tower Hamlets results in proportionate, least restrictive interventions and based on the service user’s best interests (Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2024). Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) is implemented to ensure that people in care settings are not unlawfully restricted, but backlogs and bureaucratic hurdles slow the process.

The service delivery is shaped by the Equality Act 2010, which ensures the duty to eliminate discrimination and promote equality. This legislation ensures that social care services are available for everyone irrespective of age, disability, gender, or ethnography (Mason and Minerva, 2020). This has resulted in the development of Culturally Competent Care Services in Tower Hamlets, given that the borough’s population is so diverse. Cultural sensitivities, language barriers and divergent care expectations must be aware of social workers across different cultures. It implies that assessments must be aligned to individual cultures so that care plans reflect these and the values and preferences of the service user.

The government has developed a Digital Inclusion Strategy to tackle digital exclusion for those with difficulty with technology. As a practice, this has provided community-based IT training, social worker-led digital literacy sessions, and partnerships with local organizations to make devices accessible (Mason and Minerva, 2020). But despite this, many service users in Tower Hamlets still struggle with navigating digital platforms for benefits applications, healthcare appointments, and social services, and alternative non-digital service options must still be available.

Under the Care Act, service users have greater control over their care arrangements by introducing personal budgets and direct payments. This has given the people of Tower Hamlets the opportunity to select their carer, hire a personal assistant, or receive more specific support based on their individual needs (Ali, Bell and Mounier-Jack, 2025). This has given many service users power, but ensuring that people are aware of all they can get and can manage their budgets is challenging.

Challenges and Opportunities within the Policy Framework

Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care still faces a few challenges during service delivery. Resource constraint is one of the main limitations. Budgetary constraints mean that adult social care services are unavailable, staffing levels have been reduced, and response times have been reduced in response to increased demand. Prevention and early intervention are stressed in the Care Act 2014, but funding shortfalls tend to mean that services are only allocated once people are at a critical point of need (Marczak et al., 2021).

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 is important in safeguarding rights but is also challenging to work with. Family disputes, a lack of capacity or contestation can all complicate the assessment, delay the decision-making process and heighten the demand for advocacy (Cooper et al., 2021). Procuring Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS), though, can be a bureaucratic process, and bureaucracy is a Pandora’s box of causes for administrative backlog that threaten service delivery.

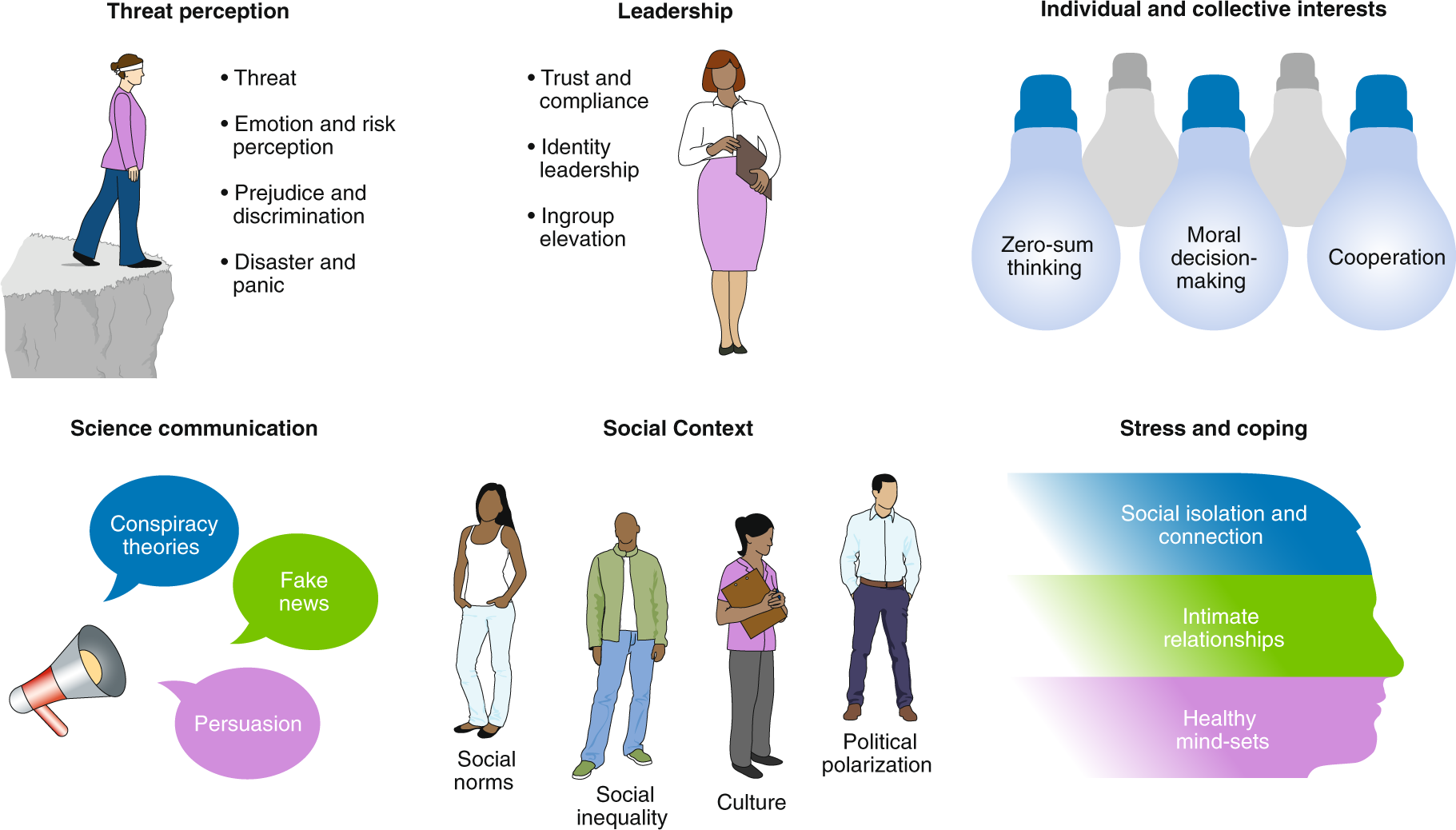

Figure 3: Influence of language model on medical triage decision making

However, although integrated care theoretically has benefits, careful and painstaking interagency collaboration creates barriers. Differences in organisational cultures, data-sharing protocols, and funding structures between health and social care commonly result in delays in service provision (Cooper et al., 2021). If somebody needs medical and social support, then lack of NHS and social care team coordination can result in fragmented care, leaving service users without timely interventions.

The policy framework provides some opportunities to improve service delivery. Promoting strength-based practice ordered under the Care Act enables social workers to foster strengths and link individuals to community-based assistance networks. With the emphasis shifted from dependency to capability and resilience, social workers can look at community partnerships, peer support networks and voluntary sector involvement (Elkady, Hernantes and Labaka, 2023). It is also important in another area of digital inclusion efforts. Also, there are possible solutions in telecare and online services. However, access and training of service users have to be improved. Community digital training through local initiatives like community-based digital training, in-home technology support and partnerships with tech organisations can work to conclude the digital divide and allow vulnerable adults to take full advantage of assistive technologies (El‐Hoss et al., 2023).

The simple processing of legislation, policies, and local service protocols defines the delivery of social work services in Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care. These include the Care Act 2014, Mental Capacity Act 2005, and Equality Act 2010, which provide the legal basis for safeguarding and supporting vulnerable adults in promoting person-centred, integrated care (El‐Hoss et al., 2023). However, resource constraints, digital exclusion, and interagency barriers hamper service delivery. Despite these, the challenges of inadequate funding, excluding people from the digital world and lack of interagency coordination continue to affect service effectiveness. The challenges notwithstanding, the policies offer the possibility of innovation, collaboration and service user autonomy, and social work in its many forms remains as vital as ever in the lives of adults in need (Jewett et al., 2021).

3. Analysis of Theories and Methods of Intervention

Strengths-Based Approach

Definition and Theoretical Basis

Strengths-based is a social work intervention in which we use the strengths and resources of an individual while ignoring deficits or limitations. This is based on positive psychology and social work theories focusing on empowerment, self-determination and resilience. This starts to challenge existing deficit-based models of care that are focused on pathology, dependency, and dysfunction (Tryphena et al., 2024). Instead, it urges the practitioner to work with the service user to identify her skills, support networks and personal strengths, allowing her to take a proactive role in her recovery and well-being.

Dennis Saleebey is one of the key figures in strengths-based social work and advocated that social work should accept individuals and communities as having their strengths instead of being worried about problems (Tryphena et al., 2024). Rapp & Goscha (2006) also acknowledged that strengths-based approaches help allow people to regain control over their lives by using the capacity of the individual, the family support, and resources in the community.

This follows the Care Act 2014, which mandates that adult social care promotes well-being, independence, and choice. Social workers must consider individuals’ strengths and assets during assessments and care planning and then provide interventions to strengthen citizens rather than pathologise their dependence (Zhang et al., 2023).

Application in Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care

In my placement in Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care, I brought the strengths approach into assessment, care planning, and intervention strategies. Social workers use this approach when planning care for older adults, people with disabilities, and people with mental health issues to prioritize the person’s existing skills and relationships with family members and within the community (Reynolds et al., 2022).

An example of strengths-based practice in my placement was the use and implementation of telecare and assistive technology to increase independent living. There were good reasons why so many elderly clients preferred to stay at home rather than transfer to residential care (Reynolds et al., 2022). Social workers evaluate their technological skills, safety needs, and support networks for assistive devices, such as personal alarms, automated medication dispensers, and smart home adaptations, to help them live safely in autonomously.

Furthermore, multi-agency collaboration with the voluntary sector organizations was also observed to be based on the strengths approach. Consequently, many clients benefitted from peer support groups, befriending services, and community-based activities to ensure their social inclusion and belonging (Joo et al., 2022). Clients were assisted to connect with these resources to obtain non-statutory supportive networks which enhanced mental and emotional wellbeing.

Strengths and Benefits

There are numerous advantages of a strengths-based approach in adult social care. Its primary benefit is it empowers self-determination that, shifts the focus from what can be done without the support to what can be done with it. This has been powerful in motivation to involve service users in decision-making about their care and to get greater satisfaction and better outcomes (Joo et al., 2022). It also serves another purpose: it is tied to personalization policies that permit people to customise their care plans according to their needs and preferences. They help social workers offer help to the service users to identify and use them for their strengths, building resilience and sense of agency, which is important in mental health recovery, disability support and elderly care.

Additionally, the strengths-based approach enables favourable relationships between friends and colleagues since it assists in collaboration rather than dependency between social workers and service users (Caiels et al., 2023). It builds trust and increases service engagement, reducing the probability of service disengagement and social isolation.

Limitations and Criticisms

Though the strengths-based method has benefits, it also has some disadvantages. The main criticism is that it can overlook structural barriers like poverty, discrimination and systemic inequalities (Zengilowski et al., 2023). While social workers often focus on individual strength, more significant aspects of social determinants of health, such as housing instability, unemployment or no access to services, can significantly influence health. This could lead critics to agree that reliance on personal strengths could unintentionally mean service users take on joint responsibility. Thus, the responsibility for their problems lies with them rather than with structural factors that make it difficult for them to lead fulfilling lives. A second problem is that some service users do not have any readily identifiable strengths or have no support networks (Mennella et al., 2024). It is unlikely that social workers will be able to use this approach effectively given that socially isolated people, having complex trauma, or with severe cognitive impairments might fail to identify their strengths. In such cases, a strengths-based approach might be taken for the social workers with more utilized care interventions such as adding more support and protection.

The success of the strengths-based approach also requires practitioner skill and training. To help clients see their strengths and family elders expand their abilities, social workers need to learn many things: motivational interviewing, active listening, creative problem solving, and so on (Mennella et al., 2024). However, without proper training and support, social workers might have trouble implementing this approach and end up with improper solutions or release statutorily ideal care plans.

Narrative Approach (Crisis Intervention Framework)

Definition and Theoretical Basis

The social work intervention narrative approach is how people tell stories concerning their lives and experiences (Gregory, 2023). Based on constructivist psychology and social work theories, people make sense of their lives by listening to stories. It is, therefore, rooted. Michael White and David Epston developed the approach with the idea that people are not defined by what is wrong with them because what is wrong with them is defined by the meaning they give to their experiences. Narrative therapy facilitates the externalization of problems, reinterpretation of experience, and the construction of new, empowering stories that foster resilience and personal agency (Pereñíguez et al., 2025).

The narrative approach is beneficial in social work practices such as crisis intervention because it allows people to understand and process sudden distressing events. In crisis intervention theory by Gerald Caplan, people in crisis are in temporary disequilibrium, which happens when they fail to use their usual coping methods (Pereñíguez et al., 2025). If clients are having difficulties, social workers immediately help them regain some sense of stability with practical and emotional validation. In cases when service users experience sudden changes in either circumstances or mood, including the housing crisis, safeguarding risk, medical emergency, or mental health breakdown, narrative and crisis intervention approaches intersect (Wang and Gupta, 2023). Integrating narrative techniques and crisis intervention can empower individuals to regain the ability to make sense of and take actionable steps to solve a problem.

Application in Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care

In particular, the narrative approach was helpful in my placement in Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care in duty system crisis interventions. According to the duty system, each team member has to work a week in the office, taking urgent calls, making emergency referrals, and safeguarding concerns (Sovold et al., 2021). A crisis call to social workers requires immediate assessment of the risk of need, determining an appropriate response and initiating interventions.

For instance, a client in a severe mental health crisis and housing contacted the service. He was evicted, he had no support network, and the thoughts of suicide were becoming increasingly heavy. By de-escalating his distress using this approach, we could focus on practical solutions: arranging emergency accommodation, talking to the mental health crisis team, and seeing him for a follow-up assessment for long-term support (Flaubert et al., 2021).

Strengths and Benefits

By offering immediate emotional relief by way of people being able to have theirs in a structured way, the narrative approach is one of the key benefits of the approach in crisis intervention. Externalizing the problem can help many clients in crisis feel overwhelmed and powerless, which can help them start to see solutions and pathways forward (Royal College of Anaesthetists, 2023). This approach is practical because it provides security in places that may feel like a trap to service users and places them in abusive or unsafe environments. Social workers can guide them towards alternative perspectives and identify patterns of resilience and change by exploring their personal narratives.

Finally, narrative work strengthens the multisectoral collaboration in crisis response. For example, in Tower Hamlets, social work with mental health teams, housing services, police and emergency medical staff is part and parcel of social work. Through narrative techniques to obtain information and assess risk, social workers can offer a more all-encompassing understanding of the service user’s needs within all-encompassing interventions (Robb and Mccarthy, 2022). Also, the approach is flexible and applicable to various service user groups. Social workers can use the narrative framework to support individuals with mental health crises, older adults, and those experiencing housing instability in ways that are person-centred and empowering. The narrative framework provides an opportunity to name previously unseen structural power relations and how the delivery and receipt of social services perpetuate them (Tadic et al., 2020).

Limitations and Criticisms

The narrative approach does, however, have disadvantages mainly because it involves a level of cognitive and emotional engagement that some crisis service users may be unable to do. At the time of intervention, individuals who are severely distressed, psychotic, or are experiencing acute trauma may not be capable or willing to think about the meaning of their narratives (Campodonico, Varese and Berry, 2022). Sometimes, crisis management involving practical and solution-focused work may take precedence over narrative work.

Another challenge is that narrative approaches are usually time-consuming. At the same time, crisis intervention is very time-limited and requires much-simplified decision-making and quick action (Campodonico, Varese and Berry, 2022). In the duty system, social workers must strive to satisfy the immediate, output-based demands of the organization while finding the time to do more reflective work.

In addition, narrative work may be practical on a cultural level. Several service users may have backgrounds where emotional expression is discouraged and might have difficulty engaging in storytelling-based interventions (Sparrow and Fornells-Ambrojo, 2024). Since narrative techniques are a social worker’s implement, they have to be used in accordance with an individual’s comfort level and verbal style to be a culturally competent, flexibly adjusting social worker.

Comparison of the Two Approaches

Differences in Focus and Application

The strength-based approach is primarily used in care planning, assessments and ongoing social work intervention. It is oriented to identify service users’ existing capacities of strength, ability and support systems that allow them to function independently and retain their well-being (Sparrow and Fornells-Ambrojo, 2024). This was especially useful when working with older adults and individuals with disabilities so they continue actively participating in decision-making and service planning.

Whereas in the narrative approach to crisis intervention, service users are in immediate distress or a crisis situation, the crisis intervention approach is used. This method grants the individual a way of processing traumatic or challenging experiences, the opportunity to externalize problems and to acquire a more positive approach (Calhoun et al., 2022). For urgent duty calls, mental health crises, or emergency housing cases, narrative-based interventions were critical in Tower Hamlets. The strengths-based approach is long-term and preventive and helps sustain and improve the individual's quality of life (Bryngeirsdottir and Halldorsdottir, 2021). In contrast, the short-term narrative approach helps treat distressing psychological situations for immediate psychological relief and crisis resolution.

Effectiveness in Addressing Client Needs

The strengths-based approach assures those with disabilities, chronic conditions, or long-term care needs that they can maintain autonomy, involve themselves with the community and even build resilience. I placed myself with older adults who were reluctant to take more support. Using a strengths-based perspective, I assisted them in identifying ways to remain independent while receiving necessary care, such as assistive technology and community networks of support.

However, the narrative approach is suitable for somebody who’s very distressed, suddenly losing her job, having a mental health breakdown, or being in an abusive situation (Bryngeirsdottir and Halldorsdottir, 2021). I would encounter service users feeling lost and having too little power over their circumstances during duty weeks. I coached them to reframe their experiences to help them move towards the business of practical solutions, such as accessing crisis accommodation, mental health services, or reuniting with estranged family members.

Strengths and Limitations of Each Approach

The strengths-based approach has several benefits, including promoting independence, increasing motivation, and being consistent with person-centred policies such as the Care Act 2014 (Caiels, Milne and Beadle-Brown, 2021). Nevertheless, it can fail to consider poverty, discrimination, or lack of resources. The narrative approach in crisis intervention is a practical approach to de-escalate distress and immediate support that is priceless in post-crisis and emergency response situations. Although it has limitations for long-term care planning, it helps with short-term crisis resolution rather than sustained change. In addition, not all service users may be capable of undertaking narrative work in a crisis, especially those with significant distress, psychosis or trauma responses (Caiels, Milne and Beadle-Brown, 2021).

Use of the Two Approaches in Social Work Practice

In practice, the two approaches can be based on merging. Narrative-based crisis interventions lead to strengths-based care planning in my placement. In one example, the service user was eventually enabled to live independently through a strengths-based model where a housing crisis was resolved following emergency intervention, supported by engagement in long-term accommodation, re-establishment of a support network and acquisition of independent living skills (Byrne and O’Mahony, 2020).

Don't let challenging assignments hold you back! Our Online Assignment Help provides you with top-quality writing assistance, detailed research, and original content that guarantees better grades and stress-free studying.

4. Review of Social Work Literature

Research has been an important area of study, particularly about learning how to most effectively intervene and achieve desirable outcomes with different client groups and policy implications. Social work practice for adult social care in urban and diverse areas such as Tower Hamlets is characterised by an intersection of legal frameworks, theoretical models and empirical research (Tower Hamlets, 2025). This literature review will explore the existing social work research linked to strengths-based practice and this narrative approach in the context of crisis interventions in relationship with the outcomes for adults with mental health challenges, older adults and individuals under social exclusion. In addition, this review will discuss the history of these interventions, their evidence base in modern practice, and how they accord with the policies and statutory responsibilities of adult social care (Aujla et al., 2023). Moreover, it will point out the gaps in the previous studies and suggest some areas to be investigated to serve this client group better.

Strengths-Based Practice in Adult Social Care

The adult social care strengths-based approach is founded on the notion that individuals already have strengths, skills and resources that can be used to enhance their wellbeing. This approach is instead around being active in helping people shape their support plan instead of identifying what they don’t have and what is lacking. The social worker's role shifts from being a provider of care to a facilitator who assists people in defining what kinds of things they can do, among other people, and in the community to be independent and live a quality of life (Rahim, 2024).

Social care assessments and interventions within this framework are informed by person-centred practice, which means social care focuses on what is essential to the individual (Jobe, Lindberg and Engström, 2020). It calls for autonomy and self-determination as opposed to traditional dependency models. For example, in adult social care, this would involve working with older adults, people with disabilities, or people with mental health challenges to help them understand ways they can lead fulfilling lives with the appropriate support in place.

In practice, strengths-based social work is used in care assessments, interventions, and long-term support planning. When assessing service users' needs, social workers look at what they find challenging and their capabilities, interests, and social connections (Lamponen and Aarnio, 2024). For example, they could determine whether an individual can perform day-to-day tasks with minor alterations instead of believing they require full-time help.

For example, in Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care, many older people want to put off residential care as long as possible and remain in their own homes. Social workers work with them through strengths-based assessments to discover how to remain independent. Assistive technology, modifying their living environment, and seeking assistance from local community organisations are all possible choices (Jobling and Sayuri, 2023). Rather than just juggling home care services, social workers try to find out what other resources are readily available to the patient to sustain their independence.

The approach is also valid for people with mental health challenges. Strengths-based practice not only focuses on the child's diagnosis and limitations but engages with them to help them take control of their lives. Social workers encourage them to reconnect with their skills, aspirations, and networks, such as identifying activities that make them well, finding activities involving voluntary or employment that fit their strengths, or supporting relationships that offer emotional support (Cabiati, 2021).

One key benefit of the strengths-based approach is that it gives service users a central role in their care. This helps to provide them with a sense of control, particularly for adults, who value that decisions about their lives are being made for them (Saar-Heiman, 2023). Personhood and participation in the care process are more likely when people can see their potential and influence their care.

Furthermore, this practice enables better long-term results. People are more resilient and confident in managing their needs when they rely on strength instead of external support (Liu et al., 2021). Such measures help decrease the need for crisis interventions and emergency services because it becomes easier for people to address a problem before it intensifies. Furthermore, it creates a more collaborative relationship between social workers and service users. Rather than simply regarding professionals as the sole decision-makers, strengths-based practice collaborates with competency-based practice in that people bring their knowledge and experience to the care planning process (Liu et al., 2021). Such an approach aligns with the social care personalisation agenda in that support is personalised to meet the needs of the individual and does not follow a one-size-fits-all approach.

However, strengths-based practice also has clear challenges. A significant weakness is that not everyone has easily visible strengths or a support network. Additionally, some service users may be isolated socially, have long-term conditions making them unable to exercise independence, or lack the financial funds to obtain further assistance (Fakoya, McCorry and Donnelly, 2020). A strengths-based approach may not be sufficient in these cases, and we may need more structured interventions.

Narrative Approach in Crisis Intervention

The social work narrative approach is grounded on the notion that people make sense of their experiences in the stories they recount about themselves and their lives. If people go through crises, they feel these stories are overwhelming and even lead to sensations of powerlessness, hopelessness, and distress (Fakoya, McCorry, and Donnelly, 2020). The narrative approach facilitates people's externalising of their problems, reframing their experiences, and rewriting their narrative, which helps build resilience, self-efficacy, and emotional recovery.

During a crisis, people may feel stuck in negative or disempowerful narratives. The narrative approach permits them to distance themselves from the situation to process the event better, regain control over their emotions, and begin to consider alternative views of their circumstance (Tadros, Presley and Ramadan, 2024). Social workers can contribute by using conversations that draw out service users’ strengths, coping mechanisms, and past successes to alter their perceptions of their situation and start thinking about solutions. This approach is complemented by crisis intervention theory (CIT) because crises create temporary states of disequilibrium, which are not adequately handled using a person's 'normal' coping mechanisms. In such moments, immediate action is needed to avoid emotional and psychological falling apart (Tyng et al., 2017). This framework includes a narrative approach that helps individuals process their emotions, understand the experience, and regain stability.

This narrative approach was particularly relevant in Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care crisis interventions during duty system emergency responses. Each team member fulfilled their duty under the system, meaning they would take urgent calls, address concerns, and make emergency referrals, dealing with those in crisis, often individuals in crisis during homelessness, sudden health deterioration, or mental health breakdowns (Zufferey et al., 2022).

One such example was of an older adult who experienced a rapid loss in mobility and refused to accept that he needed more help (Lawrance et al., 2022). The first story of her narrative was about loss and helplessness, as she finds it difficult to accept the transition to care services as a failure. I began using narrative techniques to help her reshape her experience by focusing on how accepting support might enable her to remain independent rather than taking it away. Changing her perspective helped her to take a different approach to care planning and make more informed decisions about her required support. One case involved a middle-aged man with severe mental health issues who was only housed because the landlord evicted him. At first, he told the story of success until he could see no end, or he would define his situation as entirely unsalvageable.

The primary advantage of the narrative approach in crisis intervention is that it gives people a feeling of control and agency at times of distress. People frequently feel overwhelmed and powerless in a crisis (Lawrance et al., 2022). Social workers can assist them in externalizing the crisis and viewing it from an alternate perspective, which would enable them to see new possibilities and start taking an active step forward in resolution.

This is another benefit in that it can lower emotional distress and psychological harm. It may heighten their anxiety, fear, or self-blame. With the narrative approach, they can disentangle from the immediate emotional heft of the crisis, allowing for reflection and decision-making with greater clarity (Dwivedi, 2023). In situations involving domestic abuse, mental health breakdowns or sudden loss, this is particularly useful when emotional regulation is very important for intervention work.

Also, a narrative approach may be useful in safeguarding cases to build trust and engagement. Within this story of powerlessness and dependency, people are trapped in an abuse or neglect story (Mysyuk, Westendorp and Lindenberg, 2018). By overhauling these narratives, social workers can reposition them to inform their own safety, sense of self, strengths, and available support.

The narrative approach also helps in multi-agency collaboration. Crisis interventions were often done with mental health teams, housing services, emergency services, and voluntary organisations in Tower Hamlets. However, the narrative approach enabled service users’ needs to be communicated effectively to all agencies through a structured and meaningful understanding of the information (Mysyuk, Westendorp and Lindenberg, 2018).

With its strengths, the narrative approach has some weaknesses, especially in crises when time matters. Frequently, crises require quick action, decision-making, and solid solutions without the luxury of exposing them all to in-depth narrative contemplation (Allioui and Mourdi, 2023). In emergency settings, social workers have to listen and frame narratives while ensuring that action and crisis resolution occur quickly enough.

However, as a consequence of this last limitation, not all those in crisis can engage in narrative-based reflection at the point of intervention. For example, some service users, even those who are acutely distressed, severely traumatised, or psychotic, will be unable to express their experiences or narratively describe them (Saunders et al., 2023). This is particularly true when given the directive solution-focused and crisis intervention Strategies. Cultural factors can also be played in receiving these narrative approaches. In some cultures, it is not culturally acceptable to discuss emotions and personal experiences openly.

Gaps in Research and Future Directions

The supportive literature base in strength-based practice has grown; however, several areas should be involved in further research. One key gap is the absence of empirical studies that measure long-term outcomes for service users engaged in strengths-based interventions (Li et al., 2025). Existing research shows how self-determination, resilience, and empowerment are beneficial; however, limited data is supplied regarding whether these results will be sustainable over time (Dushkova and Ivlieva, 2024). Longitudinal studies could help discover if the people given strengths-based support will stay independent and well off in the long run or if they do go on to require additional interventions.

Another critical gap in research is how strengths-based practice interplays with systemic barriers such as poverty, discrimination and unequal access to health care. The available literature on strengths-based approaches assumes service users somehow control their circumstances. However, adult social care entails situations in which many individuals cannot become self-sufficient (Li et al., 2025). Further exploration of how social workers can merge strengths-based with systemic advocacy and policy change without setting unreasonably high expectations of individuals and without addressing broader social inequities is needed.

In addition, strengths-based models have been extensively examined in mental health and disability support but have not been studied in terms of use in digital inclusion and technology-based interventions. With the ongoing use of telecare and assistive technology in social care, additional studies could examine the potential advantages of strengths-based digital support to older adults and people with disability regarding wellness and independence (Weck and Afanassieva, 2022).

The application of the narrative approach in crisis intervention has been widely studied in therapeutic counselling contexts. However, far fewer studies relate to the application in social work emergency response environments. Currently, most studies in this area are based on long-term narrative therapy, leaving behind the question of how short, narrative-based interventions work in emergency situations in crisis, with a need for a solution in minutes (Weck and Afanassieva, 2022).

The research has another gap: the narrative approach was not tested in culturally diverse populations. However, social workers working in boroughs such as Tower Hamlets, where many service users come from different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, must adapt such a technique to be culturally appropriate (Popescu and Pudelko, 2024). However, there is little research on how culture impacts cultural norms, differences in language, and various formats of the storytelling tradition and how they affect the effectiveness of a narrative crisis intervention (Popescu and Pudelko, 2024). Future work could investigate how culturally responsive narrative work could increase engagement and outcomes for diverse service users.

In addition, encouraged by research that narrative methods can help individuals create externalization of problems and reframe their experience, research remains sparse about how these interventions affect sustained coping mechanisms (Popescu and Pudelko, 2024). There is a need to conduct more studies to explore whether or not people who engage service users seeking narrative-based crisis support develop enduring changes in their self-perception and resilience or whether their effects are short-lived.

5. Critical Distinction Between Knowledge Types

Theoretical Knowledge in Social Work

Formal concepts, models and frameworks which guide social work practice are termed theoretical knowledge. Most theories are from psychology, sociology, and law, and they contain a structured ground for understanding human behaviour, social systems, and ethical responsibilities (Miller, 2022). Theoretical knowledge is essential to determine what will be included in adult social care interventions or assessments. For example, the Care Act 2014 is based on the well-being and personalisation principle; therefore, social workers are expected to adopt strengths-based and person-centred approaches (Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2024). In my placement, strengths-based practice and narrative theory were used in care planning, crisis intervention and safeguarding decisions.

Using the strengths-based approach allowed service users' capabilities to be the focus of care assessments by recognising that interventions should promote these capabilities and not rely on service users' deficits. Just like narrative theory helped crisis intervention scenarios, it also helped service users reframe their experiences, externalise their problems, and regain control (Kohrt et al., 2020). Nevertheless, knowledge only in theory was not sufficient in my practice. It offered a framework for decision but needed adaptation to service user preferences, real-life complexities, and ethical considerations.

Practice-Based Wisdom

Practice-based wisdom refers to knowledge gained from real-life experiences in social work settings. It differs from theoretical knowledge, which is mainly learnt through education and training (Kerr, Deane and Crowe, 2019). Unlike theoretical knowledge, practice-based wisdom is gained through repeated exposure to real-life cases, professional interactions, and on-the-job learning.

In the placement, practice-based wisdom was absolutely essential when there was no neat fit of a theoretical model to complex social work cases. One case was responding to the service users unwilling to accept care interventions, especially the older ones resisting the change to assisted support (van Sambeek et al., 2021). Theoretically, lower-intensity strengths-based practice could be aided by talking about the autonomy and independence of service users and encouraging them to participate in their care. In reality, however, many people were resistant, mainly because of a cultural value or experience with social services or because they feared losing control over their lives (Bostanli and Habisch, 2023).

This was one of a series of examples of practice-based wisdom in crisis intervention settings. The theoretical model of crisis intervention is transparent in its onset, from assessing risk to de-escalation and finally providing immediate support. In reality, however, crises are usually unpredictable and must be decided upon in moments, relying on intuition and experience and assessing risk factors in real time (Deverell and Ganic, 2024). This enabled me to see how experienced social workers used their professional expertise to decide when to insist on immediate action and when to wait until a service user had time to consider the information.

Evidence-Based Practice in Social Work

Evidence-based practice (EBP) includes research-based practice, best practice, and professional expertise to guide intervention (Deverell and Ganic, 2024). EBP is the adult social care use of proven strategies to achieve the best outcomes for service users within adult social care.

Evidence-based practice was at the centre of my placement, covering mental health interventions, safeguarding decisions and deploying telecare solutions. Assistive technology, including fall detectors and medication management systems, enhances independence and safety in older adults (Kieu and Senanayake, 2023). This research had to be applied in practice by assessing those service users susceptible to falls or non-adherence to medication using these digital interventions.

The evidence-based safeguarding models such as the Strengths and Signs of Safety Framework were adopted in assessing risks of abuse and neglect of vulnerable adults. This meant working closely with health professionals, police, housing officers, and mental health teams to coordinate interventions, as research indicates that multi-agency approaches are more effective in managing safeguarding interventions (Reale et al., 2023). This posed the challenge of applying evidence-based practice to ascertain the context relevance of research findings. However, real-world applications must be adjusted to resource availability, service user preferences and socio-cultural factors, and many studies have been conducted in controlled settings.

Reflective Knowledge and Self-Reflexivity

Critical self-evaluation of practice develops reflective knowledge that social workers can use to learn from experience and be ready to improve their approach. Reflexivity takes it a step further by encouraging practitioners to counter their biases, associations, and assumptions to prevent their practice from being unethical and person-centred (Gregg et al., 2022).

However, that reflective knowledge was used to adapt my approach to different service users during my placement. For example, I interacted with a person who had had many adverse events with social services. The thing is, it was initially challenging them to trust, as he just would not engage. Overthinking it all, I realized that I had done it from a professional point of view rather than a relational one, where I should be focusing on assessments and how to go about the whole process of figuring it out and how to proceed from here, instead of focusing on how to build rapport and listen empathetically. I adjusted my approach to build their trust and develop a care plan they were more likely to buy into.

This also needed to include reflective practice when emotionally vulnerable cases were faced. Sometimes, it was hard to separate professional responsibility from emotional involvement when doing crisis intervention. Reflective supervision sessions enabled me to reflect on these challenges and develop healthier coping methods with professional boundaries (Muthanna and Alduais, 2023).

Service User Knowledge and Lived Experience

Lived experience is knowledge obtained directly from people who have lived through social problems, crises, or long-term care needs. Service user voices were an essential priority in the care planning of Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care (Roberts et al., 2019). Some interventions were co-produced alongside service users and reflected their lived experiences, cultural backgrounds, and personal preferences in decision-making.

One such example entailed assisting an older adult with a disability who initially rebuffed home care services. In this effort, they preferred not to impose a given care plan but rather to enter conversations around what independence meant to them and to make the proposed intervention with their lives in check (Parry, 2024). This resulted in another support arrangement encompassing technological support and peer support, sourced from a community group, that, based on their values, was still available to them and provided with the necessary care.

6. Conclusion

This report has discussed how policies, theories, intervention methods, and research contribute to practical social work practice in Tower Hamlets Adult Social Care, emphasising older adults, the disabled, and people with mental health problems. Reviewing the legislative frameworks, intervening models, and knowledge types shows that social work practice demands a multiphased approach that uses law and order, theoretical base, practical experience, and service user engagement.

The Care Act 2014, Mental Capacity Act 2005, and Equality Act 2010 provide the basis for safeguarding and promoting well-being within adult social care. Such policies emphasise a person-centred approach, strengths-based approach, and integrated service delivery, and these interventions are under ethical and professional standards. However, service effectiveness is hindered by resource constraints, digital exclusion and inter-agency coordination issues. Addressing these challenges calls for imaginative problem-solving, advocacy, and constant adaptation of practice to meet the variety of users' needs.

This report examined two key intervention models explored: the strengths-based approach and the narrative approach within the crisis intervention. The approach is strengths-based, empowering people, building resilience, obtaining views, and involving service users for long-term independence and self-sufficiency. However, the narrative approach in crisis intervention is more immediate and responsive. It facilitates the service user's redefinition of experience, externalisation of the problem and attempts to regain control in moments of distress. At my placement, both models were of value in different settings, strengths-based practice for care planning and service user autonomy, and narrative approach in duty system crisis interventions and safeguarding cases.

These intervention models were based on a literature review of social work literature, which provides that these approaches were practical. Still, there are gaps in the research and areas of improvement. The strength of this approach, which has been studied to improve engagement, well-being, and independence, is that it is more sustainable regarding long-term outcomes; there is little research to date. Similarly, stories in the therapy literature are well-researched, but there is a relative paucity of empirical documentation on their use in crisis intervention in adult social care. Given the diversity and underresourcement of communities, future research should examine how these models can be integrated to formulate a more person-centred approach.

Practical Implications for Future Social Work Practice

Several lessons will reflect the future social work practice as we reflect on my placement experience. The need for adaptability is one of the most critical insights. Policies and theories give necessary guidance, but the practical reality leaves room for creative, professional problem-solving and tailor interventions to that individual's needs (Mysyuk, Westendorp and Lindenberg, 2018). In the future, I will use strengths-based methods to empower the service users. At the same time, I will mentally keep reminding myself that systemic barriers within the system might prevent them from accessing independence opportunities.

I took away the importance of critical reflection and always learning. Self-reflexivity informed my understanding of my biases, how I went about my work, and how I was with service users throughout my placement. Reflective supervision, ongoing training, and collaborative learning will be the bases of my growth as a social worker.

Further, I have increased my understanding of how multi-agency collaboration serves the connection of the line, the mission, and the people. Good social work doesn’t work in a vacuum; it relies on a working alliance with other healthcare staff, housing services, voluntary organisations, and the health people around. This placement confirmed the need to voice the service users in different systems to be offered coordinated and holistic support.

References

- Ali, I., Bell, S. and Mounier-Jack, S. (2025). ‘It was just the given thing to do’: exploring enablers for high childhood vaccination uptake in East London’s Bangladeshi community—a qualitative study. BMJ Public Health, [online] 3(1), p.e001004. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjph-2024-001004.

- Allioui, H. and Mourdi, Y. (2023). Exploring the Full Potentials of IoT for Better Financial Growth and Stability: a Comprehensive Survey. Sensors, [online] 23(19), p.8015. doi:https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/23/19/8015.

- Ariyo, K., McWilliams, A., David, A.S. and Owen, G.S. (2021). Experiences of assessing mental capacity in England and Wales: A large-scale survey of professionals. Wellcome Open Research, [online] 6(1), p.144. doi:https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16823.1.

- Atefi, G.L., de, E., Rosalia, Levin, M.E., Verhey, F.R.J. and Bartels, S.L. (2023). The use of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) in informal caregivers of people with dementia and other long-term or chronic conditions: A systematic review and conceptual integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 105, pp.102341–102341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102341.

- Aujla, N., Frost, H., Guthrie, B., Hanratty, B., Kaner, E., O’Donnell, A., Ogden, M.E., Pain, H.G., Shenkin, S.D. and Mercer, S.W. (2023). A Comparative Overview of Health and Social Care Policy for Older People in England and Scotland, United Kingdom (UK). Health Policy, 132, pp.104814–104814. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2023.104814.

- Bavel, J.J.V., Baicker, K., Boggio, P.S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M.J., Crum, A.J., Douglas, K.M., Druckman, J.N., Drury, J., Dube, O., Ellemers, N., Finkel, E.J., Fowler, J.H., Gelfand, M., Han, S., Haslam, S.A., Jetten, J. and Kitayama, S. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour, [online] 4(1), pp.460–471. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z.

- Bostanli, L. and Habisch, A. (2023). Narratives as a Tool for Practically Wise Leadership. Humanistic management journal, 8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s41463-023-00148-6.

- Bryngeirsdottir, H.S. and Halldorsdottir, S. (2021). The challenging journey from trauma to post‐traumatic growth: Lived experiences of facilitating and hindering factors. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 36(3), pp.752–768. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.13037.

- Byrne, G. and O’Mahony, T. (2020). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for adults with intellectual disabilities and/or autism spectrum conditions (ASC): A systematic review". Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.10.001.

- Cabiati, E. (2021). Social workers helping each other during the COVID-19 pandemic: Online mutual support groups. International Social Work, 64(5), p.002087282097544. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820975447.

- Caiels, J., Milne, A. and Beadle-Brown, J. (2021). Strengths-Based approaches in social work and social care: Reviewing the evidence. Journal of Long Term Care, [online] 0(2021), pp.401–422. doi:https://doi.org/10.31389/jltc.102.

- Caiels, J., Šilarova, B., Milne, A. and Beadle‐Brown, J. (2023). Strengths-based approaches—perspectives from practitioners. British Journal of Social Work, [online] 54(1), pp.168–188. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcad186.

- Calhoun, C.D., Stone, K.J., Cobb, A.R., Patterson, M.W., Danielson, C.K. and Bendezú, J.J. (2022). The Role of Social Support in Coping with Psychological Trauma: an Integrated Biopsychosocial Model for Posttraumatic Stress Recovery. Psychiatric Quarterly, 93(4), pp.949–970. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-022-10003-w.

- Campodonico, C., Varese, F. and Berry, K. (2022). Trauma and psychosis: a qualitative study exploring the perspectives of people with psychosis on the influence of traumatic experiences on psychotic symptoms and quality of life. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03808-3.

- Cooper, S., Schmidt, B.-M., Sambala, E.Z., Swartz, A., Colvin, C.J., Leon, N. and Wiysonge, C.S. (2021). Factors that influence parents’ and informal caregivers’ views and practices regarding routine childhood vaccination: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, [online] 2021(10). doi:https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8550333/.

- Deverell, E. and Ganic, A. (2024). Crisis and performance: A contingency approach to performance indicators. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 105, pp.104417–104417. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104417.

- Dushkova, D. and Ivlieva, O. (2024). Empowering Communities to Act for a Change: A Review of the Community Empowerment Programs towards Sustainability and Resilience. Sustainability, [online] 16(19), p.8700. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198700.

- Dwivedi, Y.K. (2023). ‘So what if ChatGPT wrote it?’ Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 71(0268-4012), p.102642. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102642.

- El‐Hoss, T., Thomas, F., Gradinger, F. and Hughes, S. (2023). The role of the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector in Early Help: Critical reflections from embedded social care research. Child & Family Social Work, 28(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.13034.

- Elkady, S., Hernantes, J. and Labaka, L. (2023). Towards a resilient community: A decision support framework for prioritizing stakeholders’ interaction areas. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, [online] 237, p.109358. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2023.109358.

- Equality and Human Rights Commission (2020). Your rights under the Equality Act 2010. [online] www.equalityhumanrights.com. Available at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/equality/equality-act-2010/your-rights-under-equality-act-2010 [Accessed 17 Mar. 2025].

- Fakoya, O.A., McCorry, N.K. and Donnelly, M. (2020). Loneliness and Social Isolation Interventions for Older adults: a Scoping Review of Reviews. BMC Public Health, 20(1), pp.1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8251-6.

- Flaubert, J.L., Menestrel, S.L., Williams, D.R. and Wakefield, M.K. (2021). Supporting the Health and Professional well-being of Nurses. [online] www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. National Academies Press. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK573902/.

- Frishammar, J., Essén, A., Bergström, F. and Ekman, T. (2023). Digital Health Platforms for the elderly? Key Adoption and Usage Barriers and Ways to Address Them. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, [online] 189, p.122319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122319.

- Gomez, C., Yin, J., Huang, C.-M. and Unberath, M. (2024). How large language model-powered conversational agents influence decision making in domestic medical triage contexts. Frontiers in Computer Science, 6. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomp.2024.1427463.

- Gregg, E.A., Kidd, L.R., Bekessy, S.A., Martin, J.K., Robinson, J.A. and Garrard, G.E. (2022). Ethical considerations for conservation messaging research and practice. People and Nature, 4(5), pp.1098–1112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10373.

- Gregory, M. (2023). Story‐building and narrative in social workers’ case‐talk: A model of social work sensemaking. Child & Family Social Work. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.13014.

- House of Lords (2019). HOUSE OF LORDS Select Committee on the Equality Act 2010 and Disability the Equality Act 2010: the Impact on Disabled People. [online] Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201516/ldselect/ldeqact/117/117.pdf [Accessed 17 Mar. 2025].

- Isaacs, A.N. and Mitchell, E. (2024). Mental health integrated care models in primary care and factors that contribute to their effective implementation: a scoping review. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 18(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-024-00625-x.

- Jewett, R.L., Mah, S.M., Howell, N. and Larsen, M.M. (2021). Social Cohesion and Community Resilience During COVID-19 and Pandemics: A Rapid Scoping Review to Inform the United Nations Research Roadmap for COVID-19 Recovery. International Journal of Health Services, 51(3), p.002073142199709. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731421997092.

- Jobe, I., Lindberg, B. and Engström, Å. (2020). Health and social care professionals’ experiences of collaborative planning—Applying the person‐centred practice framework. Nursing Open, 7(6). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.597.

- Jobling, H. and Sayuri, S. (2023). The Impact of Service User Involvement in Health and Social Care Education: A Scoping Review. Practice, 36(3), pp.1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2023.2248414.

- Joo, J.H., Bone, L., Forte, J., Kirley, E., Lynch, T. and Aboumatar, H. (2022). The benefits and challenges of established peer support programmes for patients, informal caregivers, and healthcare providers. Family Practice, 39(5), pp.903–912. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmac004.

- Kerr, D.J.R., Deane, F.P. and Crowe, T.P. (2019). Narrative Identity Reconstruction as Adaptive Growth During Mental Health Recovery: A Narrative Coaching Boardgame Approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(994). doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00994.

- Kieu, L.M. and Senanayake, G. (2023). Perception, experience and resilience to risks: a global analysis. Scientific Reports, [online] 13(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46680-1.

- Kohrt, B.A., Ottman, K., Panter-Brick, C., Konner, M. and Patel, V. (2020). Why we heal: The evolution of psychological healing and implications for global mental health. Clinical Psychology Review, 82(82), p.101920. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101920.

- Lamponen, T. and Aarnio, N. (2024). Social workers’ assessment of a child’s need for services as ‘craftwork’ practice. Journal of Social Work Practice, 38(2), pp.1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2024.2302603.

- Lawrance, E.L., Thompson, R., Newberry Le Vay, J., Page, L. and Jennings, N. (2022). The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence, and its Implications. International Review of Psychiatry, 34(5), pp.443–498. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2022.2128725.

- Li, K., Bashiri, M., K Lim, M. and Akpobi, T. (2025). How to improve supply chain sustainable performance by resilience practices through dynamic capability view: Evidence from Chinese construction. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 212, p.107965. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2024.107965.

- Liu, Q., Jiang, M., Li, S. and Yang, Y. (2021). Social support, resilience, and self-esteem protect against common mental health problems in early adolescence. Medicine, [online] 100(4). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7850671/.

- Marczak, J., Fernandez, J.-L., Manthorpe, J., Brimblecombe, N., Moriarty, J., Knapp, M. and Snell, T. (2021). How Have the Care Act 2014 Ambitions to Support Carers Translated into Local practice? Findings from a Process Evaluation Study of Local stakeholders’ Perceptions of Care Act Implementation. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(5). doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13599.

- Mason, A. and Minerva, F. (2020). Should the Equality Act 2010 Be Extended to Prohibit Appearance Discrimination? Political Studies, 70(2), pp.425–442. doi:https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0032321720966480.

- Mennella, C., Maniscalco, U., Pietro, G.D. and Esposito, M. (2024). Ethical and regulatory challenges of AI technologies in healthcare: A narrative review. Heliyon, [online] 10(4), pp.e26297–e26297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26297.

- Miller, P.H. (2022). Developmental theories: Past, present, and future. Developmental Review, [online] 66(101049). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2022.101049.

- Muthanna, A. and Alduais, A. (2023). The Interrelationship of Reflexivity, Sensitivity and Integrity in Conducting Interviews. Behavioral Sciences, 13(3), p.218. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030218.

- Mysyuk, Y., Westendorp, R.G.J. and Lindenberg, J. (2018). How older persons explain why they became victims of abuse. Age and Ageing, [online] 45(5), pp.695–702. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw100.

- Parry, R. (2024). Communication in Palliative Care and About End of Life: A State-of-the-Art Literature Review of Conversation-Analytic Research in Healthcare. Research on language and social interaction, 57(1), pp.127–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2024.2305048.

- Pereñíguez, M.D., Palacios, J., Echevarría, P., Morales-Moreno, I. and Muñoz, A. (2025). The Use of Narratives as a Therapeutic Tool Among Latin American Immigrant Women: Processes of Reconstruction and Empowerment in Contexts of Vulnerability. Healthcare, 13(4), p.362. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13040362.

- Popescu, C. and Pudelko, M. (2024). The impact of cultural identity on cultural and language bridging skills of first and second generation highly qualified migrants. Journal of World Business, 59(6), pp.101571–101571. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2024.101571.

- Rahim, R. (2024). Social workers’ role in the provision of services for families with children and youth with disabilities in Latvia, Slovakia, and Portugal. SHS Web of Conferences, [online] 184, p.01007. doi:https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202418401007.

- Reale, C., Salwei, M.E., Militello, L.G., Weinger, M.B., Burden, A., Sushereba, C., Torsher, L.C., Andreae, M.H., Gaba, D.M., McIvor, W.R., Banerjee, A., Slagle, J. and Anders, S. (2023). Decision-Making During High-Risk Events: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, 17(2), p.155534342211474. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/15553434221147415.

- Reynolds, C.F., Jeste, D.V., Sachdev, P.S. and Blazer, D.G. (2022). Mental health care for older adults: recent advances and new directions in clinical practice and research. World Psychiatry, [online] 21(3), pp.336–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20996.

- Robb, M. and Mccarthy, M. (2022). Managing risk: Social Workers’ Intervention Strategies in Cases of Domestic Abuse against People with Learning Disabilities. Health, Risk & Society, 25(1-2), pp.1–16. doi:https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13698575.2022.2143169.

- Roberts, S., Eaton, S., Finch, T., Lewis-Barned, N., Lhussier, M., Oliver, L., Rapley, T. and Temple-Scott, D. (2019). The Year of Care approach: developing a model and delivery programme for care and support planning in long term conditions within general practice. BMC Family Practice, [online] 20(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-019-1042-4.

- Royal College of Anaesthetists (2023). Chapter 2: Guidelines for the Provision of Anaesthesia Services for the Perioperative Care of Elective and Urgent Care Patients | The Royal College of Anaesthetists. [online] rcoa.ac.uk. Available at: https://rcoa.ac.uk/gpas/chapter-2 [Accessed 17 Mar. 2025].

- Saar-Heiman, Y. (2023). Power with and power over: Social workers’ reflections on their use of power when talking with parents about child welfare concerns. Children and Youth Services Review, [online] 145(145), p.106776. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106776.

- Saunders, K.R.K., McGuinness, E., Barnett, P., Foye, U., Sears, J., Carlisle, S., Allman, F., Tzouvara, V., Schlief, M., San, V., Stuart, R., Griffiths, J., Appleton, R., McCrone, P., Rachel Rowan Olive, Nyikavaranda, P., Jeynes, T., T. K, Mitchell, L. and Simpson, A. (2023). A Scoping Review of Trauma Informed Approaches in acute, crisis, emergency, and Residential Mental Health Care. BMC Psychiatry, [online] 23(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05016-z.

- SCIE (2022). Mental Capacity Act 2005 at a Glance. [online] Social Care Institute for Excellence. Available at: https://www.scie.org.uk/mca/introduction/mental-capacity-act-2005-at-a-glance/ [Accessed 17 Mar. 2025].

- Social Care Institute for Excellence (2024). Assessment of needs. [online] SCIE. Available at: https://www.scie.org.uk/assessment-and-eligibility/assessment-of-needs-under-the-care-act-2014/ [Accessed 17 Mar. 2025].

- Sovold, L.E., Naslund, J.A., Kousoulis, A.A., Saxena, S., Qoronfleh, M.W., Grobler, C. and Münter, L. (2021). Prioritizing the Mental Health and well-being of Healthcare workers: an Urgent Global Public Health Priority. Frontiers in Public Health, 9(1), pp.1–12. doi:https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8137852/.

- Sparrow, R. and Fornells-Ambrojo, M. (2024). Two people making sense of a story: narrative exposure therapy as a trauma intervention in early intervention in psychosis. European journal of psychotraumatology, 15(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2024.2355829.

- Tadic, V., Ashcroft, R., Brown, J. and Dahrouge, S. (2020). The Role of Social Workers in Interprofessional Primary Healthcare Teams. Healthcare Policy | Politiques de Santé, [online] 16(1), pp.27–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpol.2020.26292.

- Tadros, E., Presley, S. and Ramadan, A. (2024). Dear John: Letter Writing as a Narrative Therapy Intervention. Trends in Psychology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-024-00413-z.

- Tower Hamlets (2025). Adult Social Care. [online] Towerhamlets.gov.uk. Available at: https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/lgnl/health__social_care/Health-and-adult-social-care/ASC/Adult_social_care.aspx [Accessed 17 Mar. 2025].

- Tryphena, K.P., Shukla, R., Khatri, D.K. and Vora, L.K. (2024). Pathogenesis, Diagnostics, and Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease: Breaking the Memory Barrier. Ageing Research Reviews, 101, pp.102481–102481. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2024.102481.

- Tyng, C.M., Amin, H.U., Saad, M.N.M. and Malik, A.S. (2017). The Influences of Emotion on Learning and Memory. Frontiers in Psychology, [online] 8(1454). doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01454.

- UK Government (2018). Code of Practice Mental Capacity Act 2005. [online] Gov.uk. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5f6cc6138fa8f541f6763295/Mental-capacity-act-code-of-practice.pdf [Accessed 17 Mar. 2025].

- van Sambeek, N., Baart, A., Franssen, G., van Geelen, S. and Scheepers, F. (2021). Recovering Context in Psychiatry: What Contextual Analysis of Service Users’ Narratives Can Teach About Recovery Support. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.773856.

- Wang, D. and Gupta, V. (2023). Crisis intervention. [online] PubMed. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559081/.

- Weck, M. and Afanassieva, M. (2022). Toward the adoption of digital assistive technology: Factors affecting older people’s initial trust formation. Telecommunications Policy, 47(2), p.102483. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2022.102483.

- Zengilowski, A., Maqbool, I., Deka, S.P., Niebaum, J.C., Placido, D., Katz, B., Shah, P. and Munakata, Y. (2023). Overemphasizing individual differences and overlooking systemic factors reinforces educational inequality. npj science of learning, 8(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-023-00164-z.

- Zhang, Y., Chen, H., Li, R., Sterling, K. and Song, W. (2023). Amyloid β-based therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: challenges, successes and future. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, [online] 8(1), pp.1–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01484-7.

- Zufferey (CZ), C., Skovdal (MS), M., Gjødsbøl (IMG), I.M. and Jervelund (SSJ), S.S. (2022). Caring for people experiencing homelessness in times of crisis: Realities of essential service providers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Copenhagen, Denmark. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 79, p.103157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103157.