Introduction Of Life Cycle Assessment Wind Turbine Assignment

Renewable energy sources are becoming more popular due to the high requirement for sustainable energy, and wind energy is one of the integral parts of green energy. Although wind energy is regarded as a renewable energy source to conventional sources of energy such as fossil fuel, it is crucial to conduct an LCA of wind energy systems for its environmental impact. LCA is a well-established approach used for including evaluation of the environmental impact of any particular system, which accompanies its use from the beginning, during the stage of raw material extraction, manufacturing, and operation to disposal or recycling. This approach assists in the comprehensive assessment of sustainability and helps in arriving at the right decision.

This study performs the LCA of Vestas V82 1.65 MWh wind turbine commonly used in onshore windpower stations and the results are calculated under the operational conditions in Penryn, UK. The computational concerns for this analysis have been based on wind speed of 8 m/s and for the variation in environmental performance, a sensitivity analysis has been performed comparing at 9 m/s. This compares to the UK electricity grid mix, an example of the electricity mix which is still dominated by fossil fuels.

The study encompasses three main LCA impact categories as follows. First, greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprint, are crucial indicators of climate change potential. Although wind energy is clean-emission some emissions occur during extraction of materials used in the production of turbines, manufacturing the turbines, installation, and maintenance. Additionally, reviewing the consideration of the non-renewable sources of energy for the depletion of fossil energy resources. Lastly, human toxicity, carcinogenic effects, covering emission in the extraction and production of the metals.

This study focuses on the assessment of wind energy’s environmental impact profile with the help of an improvement of the ReCiPe 2016 v1.03 (midpoint H) approach with OpenLCA. The facts will be useful for the development of more efficient approaches for using green energy by politicians and engineers and for organizations involved in researching this issue.

The LCA of the Vestes V82 wind turbine is conducted for the installation of wind energy system in Cornwall. The aim is to reduce the dependency on fossil fuels and make a shift towards sustainable energy mix. With the evaluation of turbine’s energy performance, the study is helpful to produce decision making for the adaption of renewable energy.

Assignment deadlines piling up? Let New Assignment Help ease your burden with expert Assignment Help in UK tailored for student success.

Methodology

Goal and Scope Definition

This study’s goal is to quantify the VESTAS V82 1.65 MWh wind turbine, electrical output per turbine at an average wind speed of 8m/s. The review is done between the LCA results of the wind turbine and the United Kingdom electricity grid mix that relies on fossil energy sources (Hampton, 2023). For comparison and considering the variability of the wind conditions, the study is conducted at 9 m/s wind speed and the outcome is compared with the base case study to check how increased wind speed affects the environmental performance.

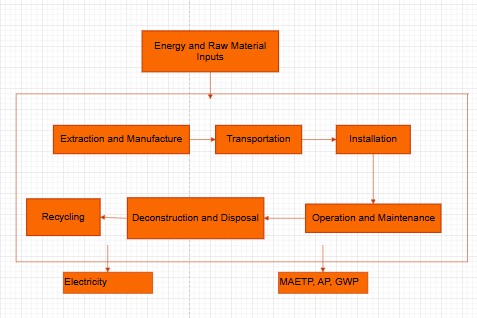

Figure 1: LCA System Boundary

This type of study involves the investigation of the lifecycle of the wind turbine. These are manufacturing of raw materials, manufacturing of the different components, transportation, installation, application, maintenance, and recycling when the final product is no longer useful. The evaluation is based on OpenLCA software with the ecoinvent database and ReCiPe 2016 v1.03 (midpoint H) impact assessment method (Nordelöf, 2024). Moreover, it is concerned with such assumptions used in the research that recycled metals represent 90% of the total metals available in the turbine, which determines the environmental conditions of the system.

Life Cycle Inventory Data

These data introduce inputs and output specifications for each perspective of the wind turbine’s life cycle at the Life Cycle Inventory (LCI).

Material Inputs:

Depending on the items used in constructing them, the V82 wind turbine contains steel, concrete fibreglass and rare earth materials like neodymium and dysprosium utilized in the generator and permanent magnet respectively (Sala and Bieda, 2022). For instance, some of these materials have an environmental influence on the carbon footprint at the stage of extracting the raw materials and during the manufacturing processes.

Manufacturing Energy:

The energy demand for material processing and manufacturing of turbines is a significant factor in LCA. Two of the most critical industries are steel and concrete manufacturing since they consume high amounts of energy thus emitting a great deal of GHG (Teffera et al. 2021). The material such as fiberglass that is used in the manufacturing of turbine blades releases less emissions but their processing is quite chemically intensive.

Operational Phase:

In the operational phase, the generation of electricity is obtained from the wind turbine at an average wind speed of 8 m/s during the capacity factor of 0.41 (Görmüş et al. 2022). The turbine works at a level that is 41% of its maximum rated electric power for the period under consideration.

| Life Cycle Stages | Components | Sub-Components | Material | Quantity (Tonnes) |

| Extraction and Manufacturing | Turbine | Rotor | Epoxy, fibre glass birchwood, Balsawood etc | 252 |

| Cast Iron | 113 | |||

| Steel | 42 | |||

| Steel Engineering (Tool Steel) | 15 | |||

| Nacelle | Cast Iron | 180 | ||

| Steel | 63 | |||

| Steel Engineering (Tool Steel) | 130 | |||

| Stainless Steel | 78 | |||

| Copper | 16 | |||

| Fibre Glass | 18 | |||

| Plastic | 10 | |||

| Aluminium | 5 | |||

| Electronics | 3 | |||

| Oil | 3 | |||

| Tower | Steel | 1260 | ||

| Aluminium | 26 | |||

| Electronics | 22 | |||

| Plastic | 20 | |||

| Copper | 13 | |||

| Oil | 10 | |||

| Internal cables | Aluminium | 3.5 | ||

| Plastic | 3 | |||

| Copper | 1.7 | |||

| Transformer | Steel | 5 | ||

| Copper | 1.3 | |||

| Transformer Oil | 2.1 | |||

| External cabels | Others | 1.1 | ||

| Plastic | 83.5 | |||

| Aluminium | 52.4 | |||

| Copper | 13.1 | |||

| Transportation | Truck | Diesel | 1120000 tkm | |

| Ship | Heavy Fuel Oil | 3600000 tkm | ||

| Installation | Tower | Concrete | 8050 | |

| Tower | Steel | 270 | ||

| Operation and Maintenance | Tap water | 101.31 | ||

| Fiberglass | 0.5115 | |||

| Resin | 0.76725 | |||

| Silica | 0.0031 | |||

| Copper | 0.3795 |

Table 1: Inventory Table

The annual energy production is subsequently calculated based on this factor; as for emissions, these are usually associated with maintenance works. Through lubricants, replacement of components, and movement of maintenance crews to and from the facilities, this phase also emits mildly.

End-of-Life Phase:

After 25 years of its use in power generation, the wind turbine is decommissioned, and the parts are recycled 90% of the metals used in the turbine are estimated to be recycled and this will reduce the emissions that might have been caused during the extraction process (Doerffer et al. 2021). However, composite materials such as fibreglass convey some degree of challenge when it comes to recycling as they are not easy to recycle. Recycling plays a major part in global environmental impact assessment as it is known to considerably contribute to lesser consumption of fossil energy and minimal emission of greenhouse gases.

Results and Discussion

Carbon Footprint and GHG Emission Reduction Potentials

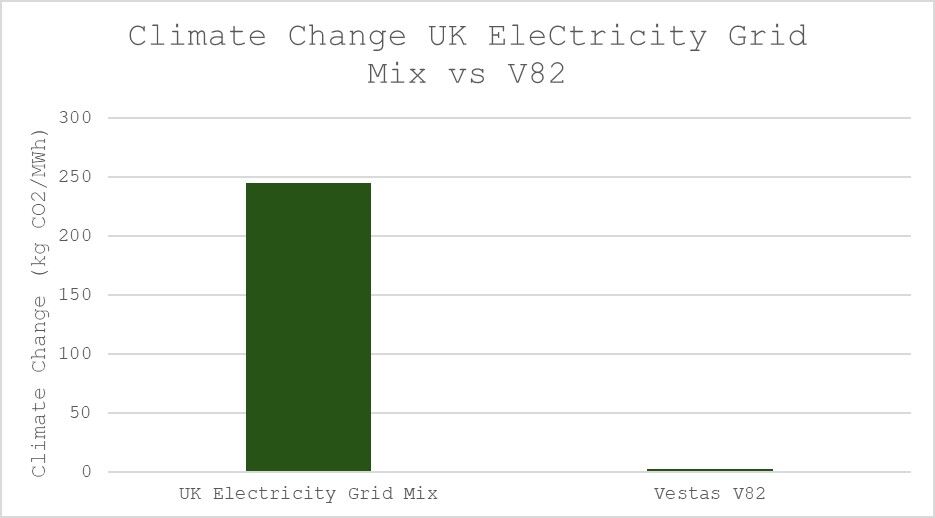

Climate Change Impact: Wind vs. Grid

Specifying the carbon footprint at a wind speed of 8 m/sec., the value makes approximately 2.5-3 kg CO₂ /MWh, which is 98% less compared to the emission of the UK electricity grid, which is about 250 kg CO₂ /MWh (Fonseca et al. 2022). At 9 m/s, that is, the conditions under which the turbine tends to operate with greater efficiency, emissions reduce to around 2.5 kg CO₂/MWh. This reduction has further been found to be very beneficial to the environment on issues of climate change.

Figure 2: Climate Change UK Electricity Grid Mix vs V82 Graph

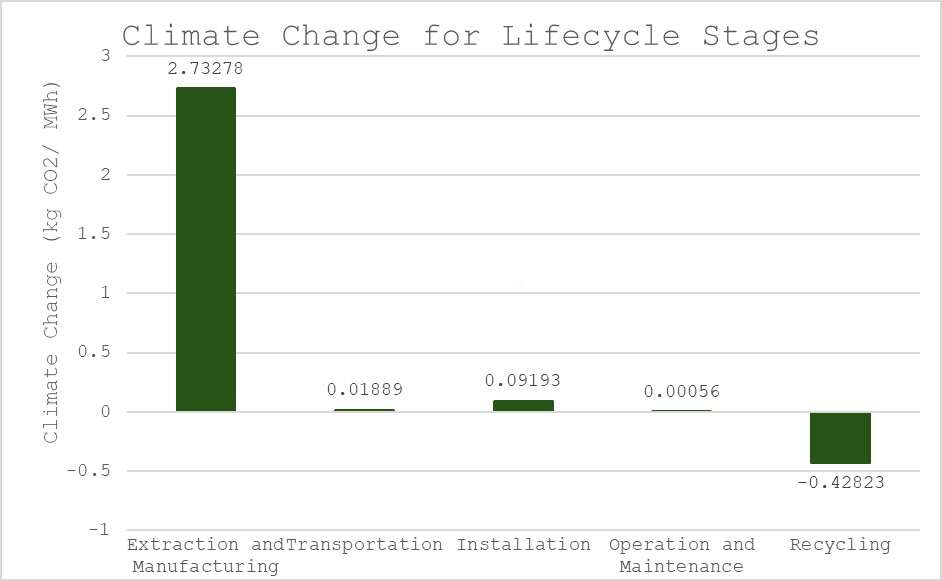

The manufacturing phase rendered high emission levels of 2.73 kg CO₂/MWh in the lifecycle of the wind turbine. This is particularly because of the power required for the manufacture of forgers such as steel, concrete and fibreglass and the magnet neodymium and dysprosium used in generator construction. However, the emissions from transportation, installation and operating the system are very low and total only up to 0.1 kg CO₂/MWh.

| Lifecycle Stage | GHG Emissions (kg CO₂/MWh) | Percentage Contribution |

| Extraction & Manufacturing | 2.73 | 91% |

| Transportation | 0.018 | 0.6% |

| Installation | 0.091 | 3% |

| Operation & Maintenance | 0.00056 | 0.02% |

| Recycling (End-of-Life) | -0.42 | -14% |

| Total (Net Emissions) | 2.5 – 3.0 | 100% |

Table 2: Lifecycle Contribution to Climate Change (GHG Emissions)

The extraction recycles itself at the end-of-life phase and contributes to the minimisation of emissions up to -0.42 kg CO₂/MWh. This is primarily because 90% of the metals are recycled, thus lowering the use necessities for new materials to be mined and processed (Spiru and Simona, 2024.). Fiberglass components also have a problem with recycling, in case of the lack of necessary technologies which causes a certain amount of negative effects on the environment.

Figure 3: Climate Change for Lifecycle Stages Graph

Another essentially important determinant that was considered while analyzing emissions in the paper includes wind speed. While at 9 m/s, the turbine produces more electricity over its lifetime hence reducing the overall emissions per MWh of energy output. This effect is because emissions from manufacturing, transportation and installation are fixed costs which when divided by a higher amount of electricity delivered give a lower carbon intensity per kilowatt.

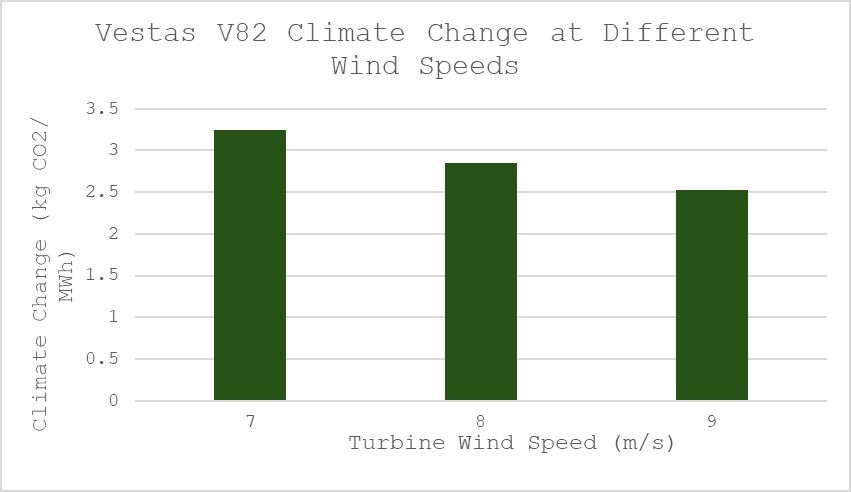

Sensitivity Analysis (Wind Speed Impact on Carbon Footprint)

The analysis aimed to range the variations of the wind speed to evaluate the effect of wind speed on GHG per unit of electricity generated by the V82 wind turbine (Huynh et al. 2025). It can be noted that it proves a tendency in the scheme:

At 7 m/s, carbon emissions are approximately 3.5 kg CO₂/MWh.

At 8 m/s, emissions decrease to 2.5–3 kg CO₂/MWh.

At 9 m/s, emissions further decline to around 2.5 kg CO₂/MWh.

Figure 4: Vestas V82 Climate Change at Different Wind Speeds Graph

This tendency could be attributed to the fact that higher wind speeds lead to enhancement of the turbine’s capacity factor leading to increased quantities of power generated within the service life of the product (Shi et al. 2021). This means that the fixed emission from manufacturing, transportation and installation is spread over a wider electricity production, and therefore the emission intensity of electricity generation is relatively lower.

The sensitivity analysis results hold implications for the site selection aspect of wind farm projects. Sites with higher mean velocities are much more beneficial in terms of environment, as the wind generator could be utilized at optimal capacity, along with the lowest overall emissions. It is highly advisable to ensure that a close-knit analysis of the wind resource and trusty planning is conducted in any wind energy project.

Other Impacts

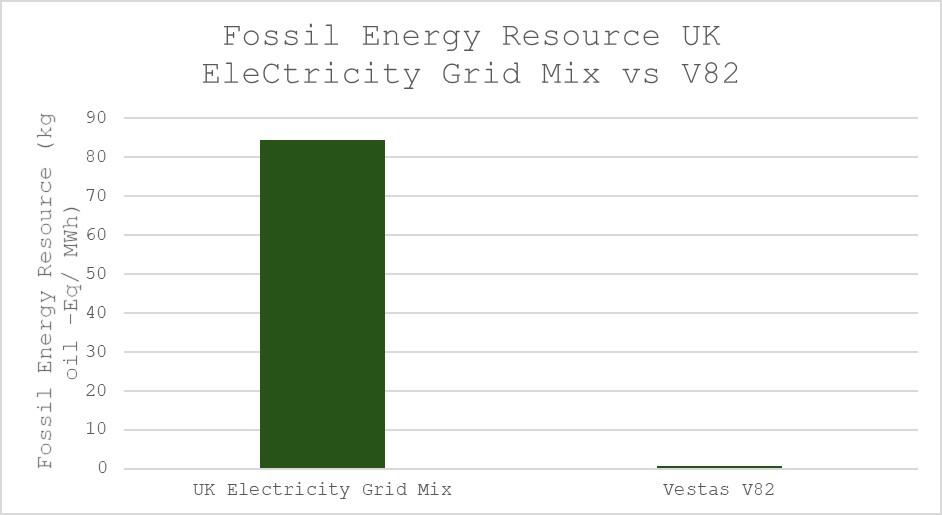

Fossil Energy Resource Depletion

It has been found that the use of wind energy can minimize the usage of fossil energy sources. The UK electricity generation in the country consists of coal, natural gas and oil-based energy where the overall fossil energy intensity is pointing towards 80-90 kg oil-equivalent per MWh of electricity produced (Atilgan and Germirli, 2024). The Vestas V82 wind power generator, on the other hand, uses fossil energy only in an insignificant volume throughout its life cycle, and can, therefore, be considered more energy-wise.

Figure 5: Fossil Energy Resource UK Electricity Grid Mix vs V82 Graph

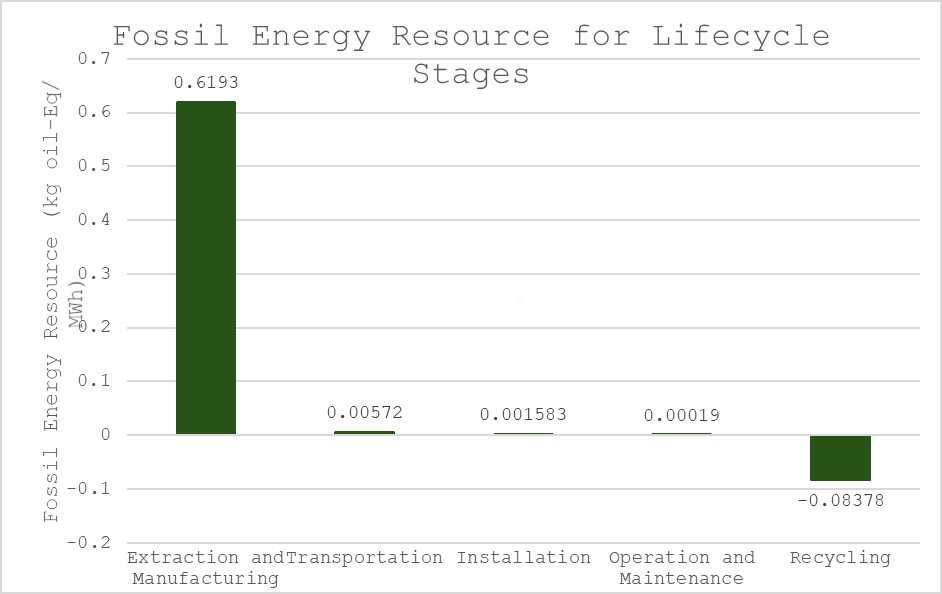

The extracted and manufacturing phase of the V82 turbine's maximum fossil energy consumption is 0.6193 kg oil-Eq/MWh. This is attributed to the fact that the manufacturing of steel, concrete, fibreglass, and several metals causes high energy consumption. Transportation, Installation and operation do not use much fossil fuel, unlike conventional power plants, wind turbines do not require constant fuel.

At the end-of-life stage, recycling plays a vital part in minimizing the demand for fossil energy. Of the metals, 90% are recycled that lead to the reduction of fossil energy consumption with a mechanized energy of (-0.08378 kg oil-Eq/MWH) (Rathore and Panwar, N 2023). This reduces by a fraction the negative effect on the extraction of the materials required to manufacture them in the first place and therefore, makes wind turbines even more sustainable in the long run.

Figure 6: Fossil Energy Resource for Lifecycle Stages Graph

Using wind energy among other forms of clean energy can help deplete the use of fossil energy resources in meeting our energy demands. The overall demand for coal, oil and natural gas is reduced due to the shift to wind energy thus overcoming some of the challenges like scarcity of resources in the energy sector, dependence on foreign countries for energy, and pollution from extraction and burning of fossil energy sources.

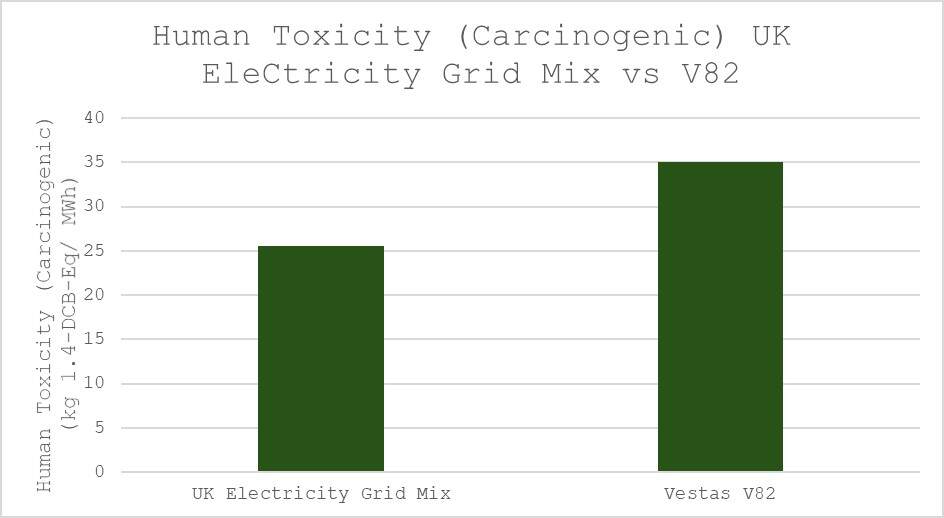

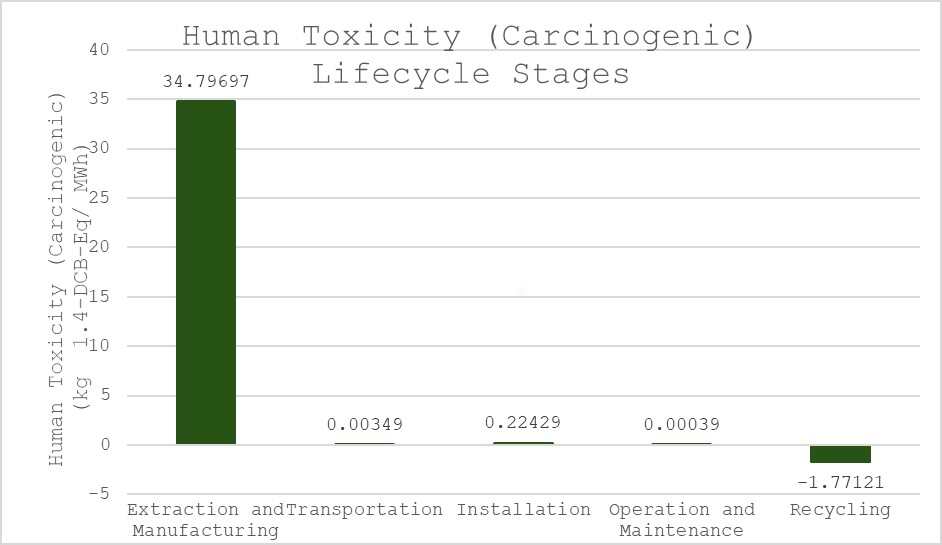

Human Toxicity (Carcinogenic) Impacts

One of the remarkable findings in the LCA of the Vestas V82 wind turbine is that the human toxicity (carcinogenic) is relatively higher compared to that of the UK electricity grid mix (Verma et al. 2022). The carcinogenic toxicity value of the studied wind turbine is estimated to be 35 kg 1.4-DCB-Eq/MWh, which is quite higher than the 25 kg 1.4-DCB-Eq/MWh which was recorded for the UK grid. This result shows the cost of relations between the environment and material extraction for the generation of electricity in stations other than hydro dams.

Figure 7: Human Toxicity (Carcinogenic) UK Electricity Grid Mix vs V82 Graph

However, in detail, the highest value of 34.8 kg 1.4-DCB-Eq/MWh is associated with the extraction and manufacturing phases of electricity production. This phase entails a lot of discharge of heavy metals, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and dangerous chemicals, which are used in processing raw materials (Almeida et al. 2023). One of the main contributors to toxicity is the use of hard-to-obtain metals that are key to the neodymium and dysprosium of the turbine's permanent magnets. These metals are mined in large quantities through processes such as acid leaching, solvent extraction and smelting; a lot of toxic byproducts are emitted into the environment.

Figure 8: Human Toxicity (Carcinogenic) Lifecycle Stages Graph

Another sector that emits carcinogenic pollutants includes the metal works industries that emit particulate matter, heavy metals such as lead and cadmium and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) resulting from refining metals and steel production. These emissions hence fall into the effects that lead to long-term emission of hazardous gases into the air, water, and even the soil.

However, by conducting an end-of-life recycling procedure, the toxicity levels can be said to be reduced to certain degrees as seen in the case of reducing the carcinogenic element by roughly 1.77 kgs 1.4-DCB-Eq/MWh (Wang et al. 2024). However, the fibreglass components, are utilised in the turbine blades or, they still pose somewhat of a challenge in terms of recycling as well as residual toxicity.

Mitigation Strategies

To that effect, the following approaches can be put in place to minimize the toxicity impact of wind turbine production:

- Sustainable Material Sourcing – Instead of utilizing virgin material sources, only 100% recyclable rare earth metals and low toxicity per-ton steel should be encouraged.

- Improved Recycling Efficiency – Another aspect of turbine blade manufacturing is the recycling of the product; with improvements in recent technology components like thermochemical decomposition or the use of better quality composites then wastage is reduced.

- Cleaner Manufacturing Processes – Renewable energy in power plants used to generate electricity makes most of the metal refining processes green.

- Environmental Regulations – It is necessary to hold the discharge of dangerous chemicals on mining and industrial processing sites to higher standards.

Although wind turbines have various benefits, such as decreasing the consumption of fossil fuels and CO2 emissions, the toxicity of wind turbines cannot be underestimated and this signifies that improvements are needed in manufacturing processes and recycling (Peri and Tal, 2021). Mitigating these issues shall help guarantee that renewable energy technologies are sustainable both in terms of environmental impact and social repercussions.

Limitations of the Study

There are some limitations which are key to discuss in detail about this LCA of Vestas V82 1.65 MWh wind turbine. The two main sources of uncertainty involved in LCA include data variability, regional grid differences, and assumptions on material sourcing and energy consumption (Fauerskov and Laurberg, 2022). Uncertainty in estimating flows could consequently influence impact estimations, especially in manufacturing and end-of-life phases.

Another limitation, in this case, is the assumption that 90% of the metals used in the turbine are recycled. Even though this assumption is in line with established industry standards, the real-life recycling rates cannot reach these figures because of several limitations caused by technological and economic considerations as well as the development of recycling industries in some geographic locations. It could lead to overestimation or underestimation of the total environmental gains due to this variation.

Operational variations affect the lifecycle emissions of the product. As the Turbine gets old, the energy which is used for maintenance, lubrication as well as the replacement of some of the components may vary and therefore may have an impact on the emissions in the long run. And, lastly, the factors including wind speed, usage of land and Local Grid characteristics in that site play an important factor contributing to the environmental performance of a wind farm (Ali et al. 2021). A location with higher wind speeds will produce a lower lifecycle emissions listing demonstrating that power plant location is crucial to achieving maximum sustainability value.

Conclusion

Recommendations

Several approaches will help to bring sustainable wind energy development to the next level. The greatest benefit of wind turbines is that they are CO2 emitting by roughly 98% less than the current UK electricity grid. This can be attributed to the need to shift to renewable energy sources in a bid to reverse some of the effects of climate change.

Greater wind velocity is beneficial to the environment because it results in increased power output of a wind turbine regarding emissions per MWh. Hence, there is a need to ensure that, to maximize power output, the suitable geographical locations that possess these characteristics are adopted.

The findings of the study reveal the following factors: one of the key issues of concern is human toxicity and resource depletion owing to the extraction of materials as well as manufacturing. As such, it becomes wise to promote sustainable mining for rare earth metals and increase efficiency in the processing of these materials. Last but not least, recycling has a great significance in determining the level of environmental footprint of wind turbines. Higher metal recycling rates and effective technologies for recycling fibreglass will advance the sustainability of wind energy systems.

Suggestions for Further Research

There is a need for additional LCA research on onshore wind turbines to fill the gaps and arrive at more comprehensive results. Therefore this indicates the need to conduct an LCA on rare earth metal extraction to examine the complete picture of the toxicity effect and resource depletion involved in the production of magnets for use in wind turbines.

Future research could also analyse various types of wind turbines, gearless vs gear-based ones to find out which difference in their components affects trailed emissions. One such field that needs to be further explored is the need to extend technologies in recycling, especially for such materials as fibreglass where there is little research on the achievable end–of–life management options.

Applying LCA to offshore wind turbines will make comparisons with onshore wind turbines, including installation, maintenance, and efficiency, possible. This will assist policymakers in having statistical information on how they can take further measures with the deployment of wind energy in the future.

Reference List

Journals

- Ali, S.W., Sadiq, M., Terriche, Y., Naqvi, S.A.R., Hoang, L.Q.N., Mutarraf, M.U., Hassan, M.A., Yang, G., Su, C.L. and Guerrero, J.M., 2021. Offshore wind farm-grid integration: A review on infrastructure, challenges, and grid solutions. Ieee Access, 9, pp.102811-102827.

- Almeida, O.A.C., De Araujo, N.O., Dias, B.H.S., de Sant’Anna Freitas, C., Coerini, L.F., Ryu, C.M. and de Castro Oliveira, J.V., 2023. The power of the smallest: The inhibitory activity of microbial volatile organic compounds against phytopathogens. Frontiers in microbiology, 13, p.951130.

- Atilgan Turkmen, B. and Germirli Babuna, F., 2024. Life cycle environmental impacts of wind turbines: a path to sustainability with challenges. Sustainability, 16(13), p.5365.

- Doerffer, K., Bałdowska-Witos, P., Pysz, M., Doerffer, P. and Tomporowski, A., 2021. Manufacturing and recycling impact on environmental life cycle assessment of innovative wind power plant part 1/2. Materials, 14(1), p.220.

- Fauerskov, M. and Laurberg, E.L., 2022. Investigation of the carbon footprint associated with offshore wind power production.

- Fonseca, L.F.S. and Carvalho, M., 2022. Greenhouse gas and energy payback times for a wind turbine installed in the Brazilian Northeast. Frontiers in Sustainability, 3, p.1060130.

- Görmüş, T., Aydoğan, B. and Ayat, B., 2022. Offshore wind power potential analysis for different wind turbines in the Mediterranean Region, 1959–2020. Energy Conversion and Management, 274, p.116470.

- Hampton, D., 2023. EAST SPARTA, OH COMMUNITY WIND PROJECT FINACIAL FEASIBILITY STUDY (Doctoral dissertation).

- Huynh, T.D., Li, F.W. and Xia, Y., 2025. Something in the air: Does air pollution affect fund managers’ carbon divestment?. Review of Accounting Studies, pp.1-28.

- Nordelöf, A., 2024. Environmental assessment of a novel generator design in a 15 MW wind turbine. Chalmers University of Technology.

- Peri, E. and Tal, A., 2021. Is setback distance the best criteria for siting wind turbines under crowded conditions? An empirical analysis. Energy Policy, 155, p.112346.

- Rathore, N. and Panwar, N.L., 2023. Environmental impact and waste recycling technologies for modern wind turbines: An overview. Waste Management & Research, 41(4), pp.744-759.

- Sala, D. and Bieda, B., 2022. Stochastic approach based on Monte Carlo (MC) simulation used for Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) uncertainty analysis in Rare Earth Elements (REEs) recovery. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 349, p. 01013). EDP Sciences.

- Shi, H., Dong, Z., Xiao, N. and Huang, Q., 2021. Wind speed distributions used in wind energy assessment: a review. Frontiers in Energy Research, 9, p.769920.

- Spiru, P. and Simona, P.L., 2024. Wind energy resource assessment and wind turbine selection analysis for sustainable energy production. Scientific Reports, 14(1), p.10708.

- Teffera, B., Assefa, B., Björklund, A. and Assefa, G., 2021. Life cycle assessment of wind farms in Ethiopia. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 26, pp.76-96.

- Verma, S.; Paul, A.R.; Haque, N, 2022. Selected Environmental Impact Indicators Assessment of Wind Energy in India Using a Life Cycle Assessment. Energies 2022, 15, 3944. https://doi.org/10.3390/ en15113944

- Wang, N., Cheng, Z., You, F., Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., Zhuang, C., Wang, Z., Ling, G., Pan, Y., Wang, J. and Ma, J., 2024. Thermal and non-thermal fire hazard characteristics of wind turbine blades. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 149(18), pp.10335-10351.